In my blogs of Halloweens (or Samhains) past, I have covered spooky goings on, mysterious folklore and bloody murders. So this year I decided to look at a whole new topic fit for the season and it’s something we have in abundance in Norwich, but seldom pay attention to; our many graveyards and cemeteries. What was once a place to contemplate mortality or spend time with the deceased has become a part of the furniture of the city, lost among the many tall, modern buildings. Many of us have walked out from Chantry Place (Chapelfield to many of us still) and cut through the graveyard directly in front without paying heed to the many headstones lining the footpath or wondered through the alley on tombland, not thinking of the many medieval skeletons laying beneath our feet. Many of these burial grounds host famous burials, quirky architecture, or creepy legends. Hopefully this blog may ignite your interest in them as, although many find them to be a little sinister, these places of remembrance can be quite peaceful to explore!

St George’s Graveyard – Tombland

If you mention Tombland in Norwich to the locals you will be met with two kinds of people. Those that know the history will tell you it was a meeting place and market for the Saxons and that ‘Tombland’ comes from the Anglo Danish and means “open space”. Others who subscribe to folklore will tell you that it is the location for a massive plague burial and that the bodies sit in their thousands beneath your feet. This latter way of thinking has proven to not be entirely true. Not only was Tombland a poor place to bury plague victims, due to it being in the centre of the city, but it’s recorded that the plague victims were more likely buried in churchyards or outside of the city walls. The rumour came around due to a chance, but horrifying, discovery in the 1970s.

Sat in Tombland is the locally famous ‘Samson and Hercules House’, a place that, in the 70s, was a nightclub but it is still well known for the two large statues standing either side of the entrance wielding large clubs. During its time as a nightclub, the venue had a cellar that held a swimming pool and downstairs bar. A man associated with the club, had been doing work in this cellar area and was digging down beneath the swimming pool when he was met face to face with the visage of a human skull. What he uncovered was not one, but six human skeletons. This would have been distressing for anyone to discover and of course this led to a lot of excitement in the local area. Once it was revealed by archaeologists that the bones were from the 14th century, people immediately linked them with the plague that devastated Norwich at that time and it was locally decided by laymen that this must have been a plague pit. It turns out, however, that these were not plague victims dumped unceremoniously into a pit, but rather burials from the St George’s Churchyard that once extended through where the buildings now sit.

There is a chance the bodies might have been those of people who died in the plague but those victims tended to be buried in regular graveyards. This is one of the reasons why so many of the graveyards, such as the one at St John Maddermarket, are raised to almost head height as you walk along them. Centuries of burials or events that involved mass death usually resulted in an influx of corpses and so they had to be stacked on top of each other with layers of ground in between which eventually raised the land level to such heights.

St George’s church still stands, albeit rather hidden behind the frontage of the more modern shops on Tombland. It can be accessed through an alleyway that runs alongside the charismatic (and wonky!) Augustine Steward House but most of what used to be the graveyard is now lost. The church itself played an important part in a piece of Norwich’s history, being the position from which rioters used slings to rain flaming missiles down on the cathedral and its buildings during the 1272 riots. It also holds the tomb of Thomas Anguish, Mayor of Norwich in 1611, who, when he died, left a considerable sum of money in his will to the city to set up an education charity, one that is still going strong today and is still known as the Anguish Educational Foundation.

If you feel like going for a look around the remaining part of the churchyard down Tombland Alley, beware, as it’s said that at dawn and dusk the ghost of a young woman in grey rags appears there. She is supposed to be the spirit of a young woman who was sealed inside her home during the 1579 plague that devastated Norwich, and only survived, being free of the plague herself, by eating her deceased parents, only to choke on a piece of her father. A grisly tale that’s fun to tickle the back of your mind while you stand among the silent, ancient stones and timbers.

The discovery of a medieval or ancient graveyard beneath a building is nothing new. England is so full of cemeteries and graveyards that have disappeared over time that it is fairly common to dig into the ground and find human bones. Just remember that the next time you decide to dig a new flower bed in the garden!

Rosary Cemetery

Rosary Cemetery is a poignant and historic cemetery for many reasons. Firstly it marks a change in how British funerary customs were conducted, moving away from religious rules to a more open and multi-faith dynamic. Rosary stands as the first truly non-denominational cemetery in Britain. To give you some background, in the early 19th Century, urban cemeteries and graveyards, including those in Norwich, were getting full. You only need to look at the height of cemeteries such as the aforementioned St John Maddermarket to see that there were bodies stacked several feet high off of the usual ground level. Fluids were leaking into nearby watercourses, used by the working people for washing, making beer and other daily elements and disease was an ever-present threat. As such, burials in church graveyards within the city walls were banned in April of 1854 by the then Home Secretary.

On top of this, Anglican Church rules at the time dictated that, for a person who was not Church of England, (whether they were Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist or any other religion or even other branches of Christianity such as Quakers, Unitarians, Catholics and Presbyterians,) would have to agree to a CoE ceremony to be buried in any church graveyard, even though they paid rates to the church. Independent cemeteries were small and often few and far between. In Norwich, the Octagon Chapel had its own Unitarian cemetery and two small Jewish cemeteries (off St Crispin’s Lane and Mariners Lane) existed. The Quakers had a larger ornate cemetery and meeting house in Gildencroft until the meeting house was sadly destroyed by a WWII Luftwaffe raid.

In the early 1800s, Reverend Thomas Drummond, a Unitarian and Presbyterian, was tired of seeing the problems with burial practices in the country and decided to open a large cemetery that could include anyone of any faith or non, victims of suicide and unchristened children. It was registered as an official cemetery as of June 1821 by Bishop Henry Bathurst of Norwich (the only Whig Bishop in the House of Lords that was so open and accepting of other people that he was described as ‘Lax in Standards’.) Most early burials were performed by Rev. Drummond with the first being his wife Ann. Previously interred in The Octagon Chapel cemetery, having tragically died in childbirth, Anne Drummond was re-buried in Rosary. The small, beautiful, gothic chapel that greets visitors from the Rosary Road side of the cemetery was added in 1879 and designed by Edward Boardman, a prominent architect in the city.

Being a collection of people from all backgrounds, the cemetery hosts many interesting figures’ final resting places. The Colman family has many members buried here, as do the Cozens-Hardys. John Barker, a steam circus proprietor who sadly was killed in a gruesome accident that saw him bisected by runaway machinery, has a tall memorial with a statue of his face looming in white from the undergrowth. A survivor of the Charge of the Light Brigade, George Wilde rests alongside the founder of the Bridewell Museum, Henry Holmes, the first chairman of the Norwich City Football Club, Robert Webster and Author of the Spanish Farm Trilogy, Ralph Hale Motrum. Two of the victims of a horrible rail accident in Thorpe near the present day Rushcutters Pub in 1874 lay side by side, John Prior and James Light. You could spend hours hunting through the greenery looking for important historical figures and everyday people.

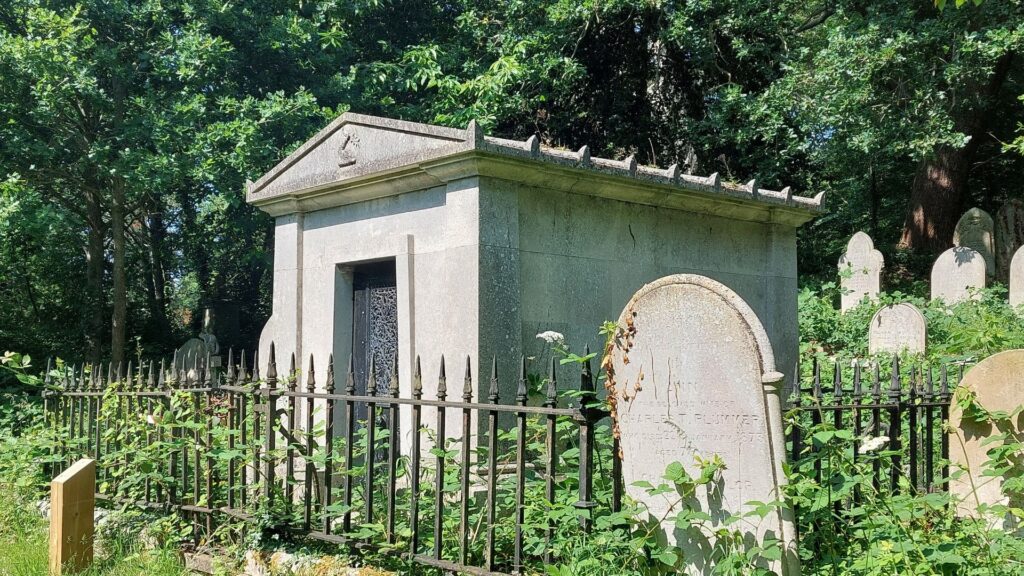

Half of the cemetery, the oldest half, has been partly left to nature. Trees hide graves from the passer-by so that you have to walk into the woodland to find them, ivy covers burials and the cemetery’s mausoleum alike, and deer and squirrels can be found amongst the headstones, running from the odd visitor and making a racket through the undergrowth.

The place has some supposed hauntings and they sound rather unsettling. Visitors have reported seeing people standing by the headstones in the undergrowth, staring at them. They don’t appear on camera (rather conveniently) and supposedly disappear when approached. A ghostly black cat has also been seen near the graves of the train crash victims that walks through the nearby wall to the newer side of the cemetery and a ghostly funeral train complete with horses and mourners has been seen making its way up the drive from Rosary Road to the chapel, disappearing once it reaches its goal. The sounds of horses neighing have also been heard around the site.

The general tudor-gothic architecture amongst the headstones brings a sense of atmosphere similar to Highgate in London, or Montmartre in Paris and together with the nature, it makes an interesting, sometimes creepy but often peaceful place to explore.

Earlham Cemetery

Following the 1854 ban on inner city burials, the city had to come up with a place to put the dead. If there’s one truth about a city, it is that there will always be dead people to bury. It was decided that a municipal (city owned) cemetery would be created. A Norwich Burial Board was created and landowners were approached by them looking for land they might be willing to sell in order to form a new cemetery. Advertisements were also put out in the local papers looking for land as well. Denmark’s Farm off of Sprowston Road and a plot off of Unthank Road were considered alongside several other sites but they were deemed unsuitable in terms of the land or the fact that they were awkward to reach with the horse drawn funerary carriages. When Mousehold Heath was considered, the people of Pockthorpe vehemently opposed it, saying they’d “rather see the furse bushes bloom than gravestones planted”. Eventually, a plot of 34 acres of farmland off Earlham Road was purchased from a Mr John Carter in 1855 thanks to a loan of £5,000 (approx £500k in today’s money) from Gurney’s Bank for obtaining the land and construction work. Plans were drawn up for grave plots, lodges and two gothic style chapels. Separate plots were drawn out for CoE burials and another for other faiths and denominations. A plot with a separate chapel was put aside for those of the Jewish Faith.

Delays, an inevitable part of any long construction project, came in the form of storm damage and a turnip crop that had to be waited upon until harvest (the most Norfolk delay possible!). Sadly, one of the workers, 32 year old James Baldry, fell while erecting the scaffolding for one of the chapels and died of his wounds. He became the first person buried in the cemetery before it even officially opened and his headstone can be found just to the southwest of the main crematorium, beside the path separating sections G and H. The cemetery officially opened on the 6th March 1856. Two superintendents were employed, living in the lodges rent free and looked after the cemetery while also acting as gravediggers. They were paid £1 a week and received 2s for every grave dug. In April of 1856, four policemen were to be stationed around the cemetery on Sundays to “keep out dogs and disreputable characters”, but that stopped as of August the same year.

Further expansion of the cemetery continued as time went on and in 1875, the burials board accepted a suggestion from a Mr J.J. WInter that a plot of land should be put aside for soldiers from the nearby Britannia Barracks and in 1876, a statue was raised to them on this plot and named “The Spirit Of The Army”. During WW2, Norwich saw heavy bombing during the Baedeker Raids and at least 235 people were killed in a very short space of time. Over a hundred of the bodies were buried in a plot of the cemetery just west of Farrow Road and after the war a memorial was placed on the site in 1946. A ceremony was held in 2012 to commemorate the 70 year anniversary of the bombings.

In 1885, cremation was made legal in the UK but as of 1945, 98% of Norwich’s dead were buried rather than cremated and with the growth rate of the population it was determined that three acres of land would be needed each year for burials leading to a plot the size of Earlham Park every 50 years and a push for cremations rather than burials was put forth as this was determined to be unsustainable. By the 1960s, cremations had become more popular and sadly this resulted in the twin chapels in Earlham Cemetery being pulled down in 1963 and replaced with the modern Crematorium.

Among the many now buried in the cemetery are some notable names such as renowned architect George Skipper, Round Table founder Louis Marchesi and artist and member of the Norwich School of Painters, John Middleton. Casualties of the South African War and 550 war dead from both World Wars are also buried here.

Gildencroft Cemetery

The Gildencroft Cemetery seated near to the ever controversial Anglia Square is a 17th Century Quaker burial ground. Quakerism is a form of Christianity that appeared in the wake of the unrest caused by the reformation under King Henry VIII. The unrest led to the rise in Puritanism which became widely popular in the 17th Century during the Civil War, especially among Parliamentarians. Puritanism was largely a belief that the new church of England wasn’t doing enough to break away from Catholic traditions or simply the belief that the new church wasn’t being built in the right way or was misinterpreting scripture. Puritan beliefs came in a range of different varieties and one of those branches became known as “The Friends”.

They believed largely in a more simplistic version of Christianity which stripped away the wealth, power and elaborate ritual for a simpler and more humanist form of the religion. They were also an order that believed holiness could be found in helping your fellow human beings and so Quakerism has been largely a force for good in its history, advocating for female ministers, gay rights and workers rights usually long before the other denominations even think about them. Sadly at the time, being non-conformists meant that Quakers suffered a lot of abuse from the authorities and public alike. Even the name “Quaker” was an insult, referencing the followers “quaking with religious madness”, but has been kept as the church as their official name today. From 1654 when they first arrived in Norwich until the late 1680s, they were attacked and beaten, meetings were broken up by authorities, goods were confiscated and stolen from them and several of them were imprisoned for their beliefs. At first, meetings took place either in the open air, hidden away on Mousehold Heath, or in private houses to avoid these attacks, and within the prison walls where a lot of the Quakers were sadly being held.

Eventually they managed to gather enough funds to open an official meeting house on Upper Goat Lane which opened in 1679 but at this time, their dead could not be legally buried in official churchyards due to the difference in religion and other arrangements had to be made. In March 1670, an acre of land was purchased by the Norwich Quakers in Gildencroft for £72 to inter their dead. Access was awful and coffins had to be carried above the heads of the pallbearers to get them into the grounds due to the narrow alley that gave them entry. Eventually land around this plot was purchased which improved access and conditions and a ‘crescent’ was put into the area outside the grounds to allow funerary carts and their horses to turn around once a coffin was delivered.

By the end of the 17th Century, Norwich had become one of the biggest strongholds of Quakers in England, with their numbers exceeding 500 people. It was decided the Upper Goat Lane meeting house was no longer sufficient and so a second meeting house was built at the west end of the cemetery in Gildencroft. It was completed in 1698 and stood proudly there until it was sadly struck by a Luftwaffe bomb during WW2, and completely destroyed. The rubble lay there until 1958, until it was decided that a new smaller and more humble meeting place would be built in its place, using, as much as they could, materials from the original structure that still littered the area. That one still stands today but by the 1970s was being used by the city as a day centre for the elderly and today it is home to the Tree House Children’s Centre but still used by the Quakers during funerals or special occasions.

Important burials include the Gurney family (bankers and precursors to the later Barclays Bank,) Elizabeth Fry the “Angel of Prisons”, and Amelia Opie, poet, writer and philanthropist whose statue looks over the street in the city named after her.

During the 19th Century, the area around the cemetery was a place to be feared. Locals were being haunted by a creature that came to be known as the “Gildencroft Bogey”. Described as a tall and gangly creature with huge slavering jaws, elongated arms with long, curved claws and eyes as big as tea saucers. According to local sources it stalked the narrow, smoggy streets around the Lathes (grain storage buildings) and leapt out and chased passers-by. It is, however, worth noting that, at the time, the area was covered in a constant blanket of thick industrial fumes and had one of the largest concentrations of pubs in the city. I’m not saying that to completely explain away the sightings but since those areas were cleared after WW2, there have been no more sightings of this monstrous creature. Maybe the bombs drove it away!

SOURCES

Invisible Works: Myths about Tombland and the Plague

Invisible Works: Rosary Cemetery

Tracy Monger: Ghosts of Norwich